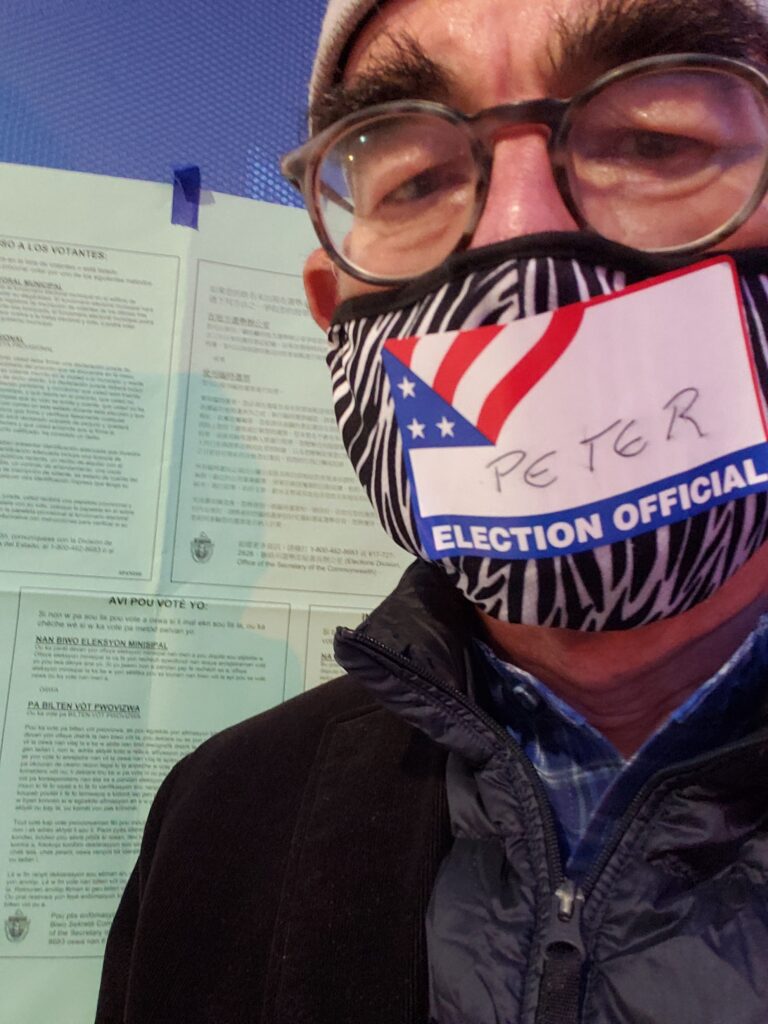

On Tuesday, I was up at 4:30 am to be at the polling place by 6 for a work stint that would go to 9:15 pm. My official title was inspector, meaning someone who does what the warden and clerk tell me. There were six other inspectors, so eight worker in all at the John Philbrick School, Roslindale, the voting place for precinct 7 of ward 18 (and my son’s first grade school).

Though the polls didn’t open till 7, people were waiting outside from 6 on as we put up signs, arranged tables, set up the voting machine-an optical scanner-and got ready to open exactly on the hour.

When the doors opened, my job was to squirt hand sanitizer and make sure people stayed 6 feet apart as they came in.

There was a little rain and sleet but the people lined up outside waited patiently. When their turn came, they gave their address to the warden who checked off their names on the voters list (and recognized most of the people even in their masks). They were given a ballot and a pen (sanitized) and went to a booth to make their choices.

Done, they went to the policeman on the other side of the school gymnasium who checked off their names against his list. Then they slid the ballot into the machine which grabbed it, and gave a little click to indicate the vote had been cast.

That was it all day. There were little rushes sometimes, but mostly a steady trickle, always someone in the back of the hall bent over a ballot figuring out who they wanted for president.

Those were the in-person voters. What about the mail-in and early voting ballots? There were about 500 of these, almost half of all the votes cast in our small precinct in this election. Mail-ins and earlys came to us in manila envelopes of fifty unopened ballots.

These each had to be checked off on the official voters list, as well as a separate list. The list indicated whether a voter had voted by mail or early. After this the ballots had to be opened and the ballots taken out, unfolded and stacked. Then the envelopes had to be checked again against the police officers list. Finally, we ran the ballots one by one through the machine. Processing these ballots happened while in-person voters were coming in, voting and leaving.

There were jams, ballots that wouldn’t go through, voters who were at the wrong place, people who weren’t registered but thought they were. There was a hard-of-seeing man who used a special machine. There were new voters helped by family members. The very young watching their parents, and very old parents helped by their children. There were excited 18 year olds, and quick-in-and-out busy voters. For me, there was a lot to see, a lot to do.

Several of my fellow inspectors had taken the day off to do this work. The warden and clerk were very experienced and kept us on task and in good spirits all through the long day.

At the end, all the ballot counts had to tally. All unprocessable ballots had to hand counted. All the ballots, nearly 1200 had to be gone through for write-ins. Everything had to be packed up in a special box for the police officer to take to City Hall. Done.

Besides my fellow workers and my fellow voters, what I encountered was a complex, labor-intensive system that I hadn’t suspected. No matter where people had voted or when, their ballots were treated as precious and duly counted, even if the ballot envelope had to be ‘touched’ a minimum of three times at the voting site, not counting the postmark on mailed-ins and the sticker with name and precinct on early vote ballots.

So many ballots and all dealt with so meticulously. And this is happening all over the city, the state, the country, handled by a dedicated cadre of poll workers. I hadn’t realized. Having spent the day being a poll worker, I’m impressed by the people, mostly volunteers, and by those who designed and oversee the process.

There’s a majesty in election day: the people speaking, making their preferences known. The machinery of making sure that voice is heard is complicated but majestic in its own way.