All around us are stories; how can we find in them accounts of encounters?

I addressed this question in the last post Dramas of livingness. Here’s the short answer: look for the dramas of livingness, which is our readiness to entertain the prospect and actually say yes to encounters.

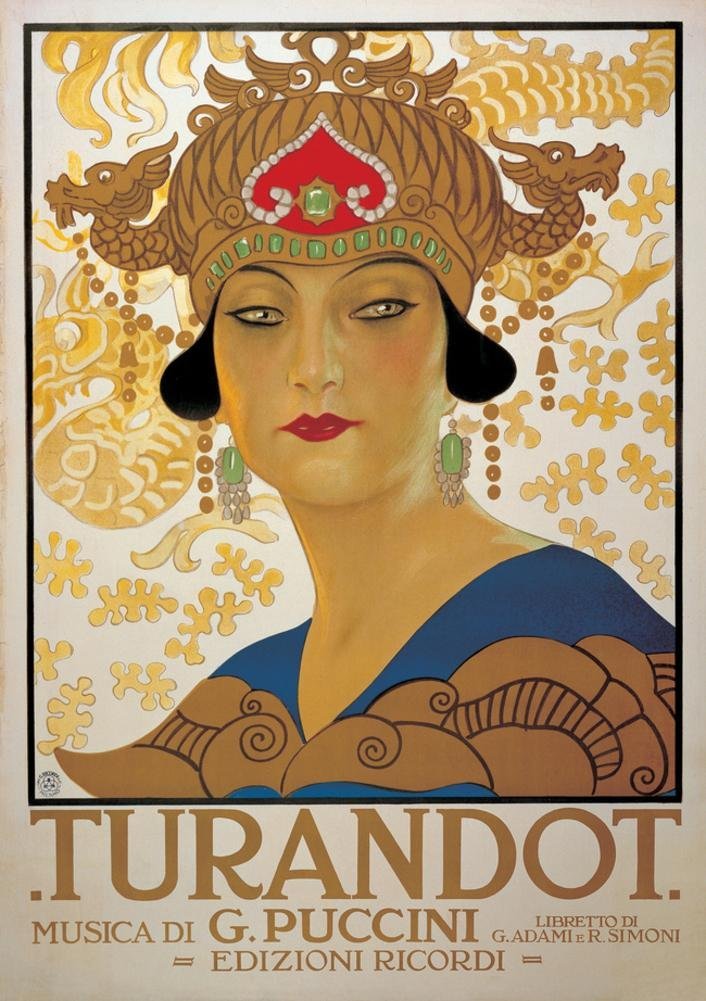

Let’s look at Puccini’s opera Turandot as an example of what I mean by a drama of livingness.

Disclaimers, to start. I am always powerfully moved by the music and (especially the Zeffirelli) production. No reserved and critical consideration as I watch and listen, no. I revel, and my eyes run.

I recognize the opera is about an imaginary Imperial China so it’s not true, not authentic, not always nice (heads on pikes), but I find it beautiful and not just as spectacle.

Finally, when I reflect, I often miss what later, when I read good critics, seems obvious or at least observable.

The opera is about the wooing of a princess Turandot who revenges the humiliation of her ancient ancestor on the suitors who show up looking to marry her. She cuts off their heads after they fail to answer the three riddles she poses them.

By the middle of the second act when she explains her motivation, we can see the setup for the drama of her livingness: she is unwilling to engage in good faith encounters with any of her suitors, and unready to even entertain the possibility of seeing them as others, not objects, of risking exposure to them, or of changing her beliefs or behaviors.

She is wooed in the opera by one Calaf who, as a Central Asian prince, is a perfect picture of those, centuries before, who conquered and violated her ancestor.

Let’s lay out the story as series of moves.

T: All who try, die.

C: Though many call me stupid, I’ll try. There’s something about her…

T: Here are the riddles, loser. (There’s something different about you, though).

C: Here are your answers: one, two, three. (Did you help me with the last one?)

T: Oh, no. My bluff has been called, but even so, I can’t (not won’t) say yes to him.

C: Okay, I solved your riddles. Now you answer mine, and if you do in time, I’ll gladly die.

T: A way out! I’ll do whatever it takes to find out (which brings me to an encounter in which I confront: a. the real possibility of failure; b. what my policy and attitudes have made me capable of (aaarh!); and c. is there something about love that I’ve been missing?)

C: Look at what kind of person you are! But you are more than this. I love you anyway.

T: You win. You hooked me on a feeling. Grrr!

C: I don’t want to conquer, so here’s the answer to the riddle. Do with it what you want.

T: Okay! I’ve got you now.

Even in this bald back and forth, the drama is clearly whether she will actually encounter Calaf and his livingness (modified by his love for her) with a willingness to actually make changes in her own. The opera ends about five minutes after this.

Oh, Puccini’s music. It haunts me.

This was a wooing story but there are so many other types of stories we tell. The weekly Metropolitan Diary in the New York Times is full of coincidental encounters. In not all of them do we see mutual encountering, but we do see the opportunities.

The travails of forgiveness animate tales of reconciliation. Dramas of mind-change are at the heart of history of science narratives. Realizations of mortality are the deep theme of memoirs.

These are accounts of encounters that can inform and inspire us. And, since all encounters invite the breeze from beyond to blow through them, they each have fresh futures forever.